Equine myopathies - PSSM 1 and MIM (“PSSM2“)

Equine myopathy is a generic term for various forms of genetically caused exertional myopathies, i.e. diseases of the musculature. PSSM stands for polysaccharide storage myopathy, whereby only type 1 (P1) describes a true storage myopathy. Other forms of myopathy are colloquially grouped under the synonym "PSSM2", because at the beginning of the research it was also assumed that this was a storage myopathy. Today, we know that "PSSM2" includes different muscle disorders, with different variants. Therefore, we now speak of MIM (Muscle-Integrity-Myopathy), which replaces the previous term "PSSM2" and more correctly describes the genetic exertional myopathy. Furthermore, the variants P2, P3, P4, Px, P8 and K1 are distinguished under MIM, with further variants likely and currently the subject of research.

However, what PSSM1 and MIM ("PSSM2") have in common is the symptomatology and the decisive influence that correct feeding and training management has on the horse's performance and, above all, well-being.

Even though this condition cannot be cured due to its genetic anchoring, feeding, training and husbandry are decisive for a painful existence or a symptom-free horse life.

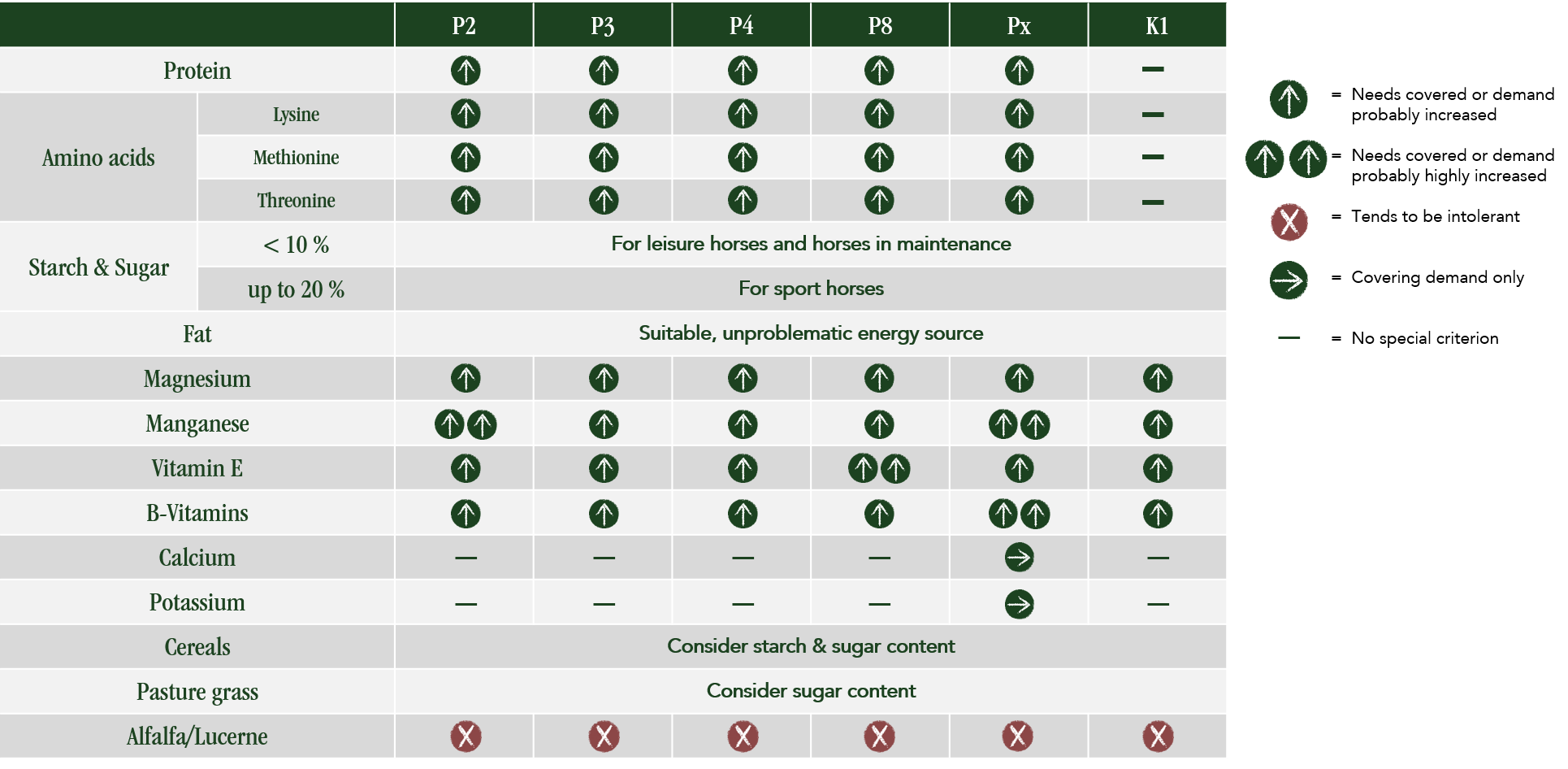

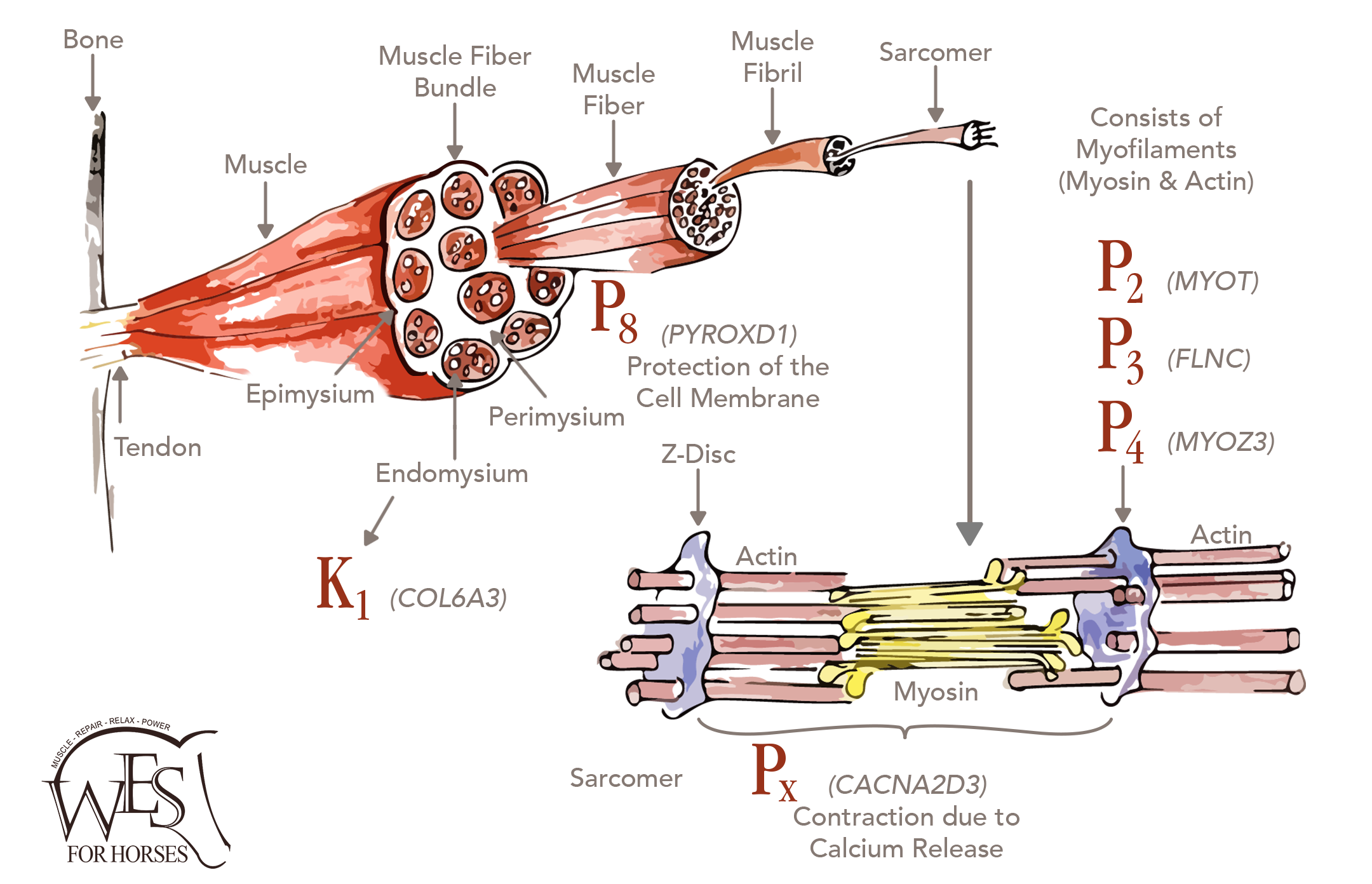

Figure 1: Overview of equine myopathy variants

PSSM 1

Polysaccharide storage myopathy, also known as PSSM1, is a genetic disease of the muscles (genetic test available). The defective gene GYS1 codes for glycogen synthase, the enzyme responsible for glycogen formation (glycogen = storage form of glucose in the animal organism) in the muscles. Glycogen synthesis leads to abnormally branched glycogen in the muscles. The uptake of glucose into the muscles is also increased due to enhanced insulin sensitivity.

PSSM1 manifests itself in symptoms similar to cruciate rash, such as muscle stiffness, jammed gait, increased sweating and even immobility. Western horse breeds and cold blood breeds are predominantly affected, although PSSM1 can theoretically occur in any breed.

Affected horses need a very strict ration for life. Starch and sugar should be < 10 % in the ration (incl. hay and pasture grass). Therefore, a grain-free ration should be aimed for. Micronutrients such as magnesium for the muscles and antioxidants such as vitamin E are helpful. Chromium should only be given as needed to avoid unnecessarily increasing insulin sensitivity (insulin activates glycogen synthase). Furthermore, these horses require adapted training with long warm-up phases. Overall, PSSM1 horses benefit from a husbandry in which sufficient moderate exercise is possible.

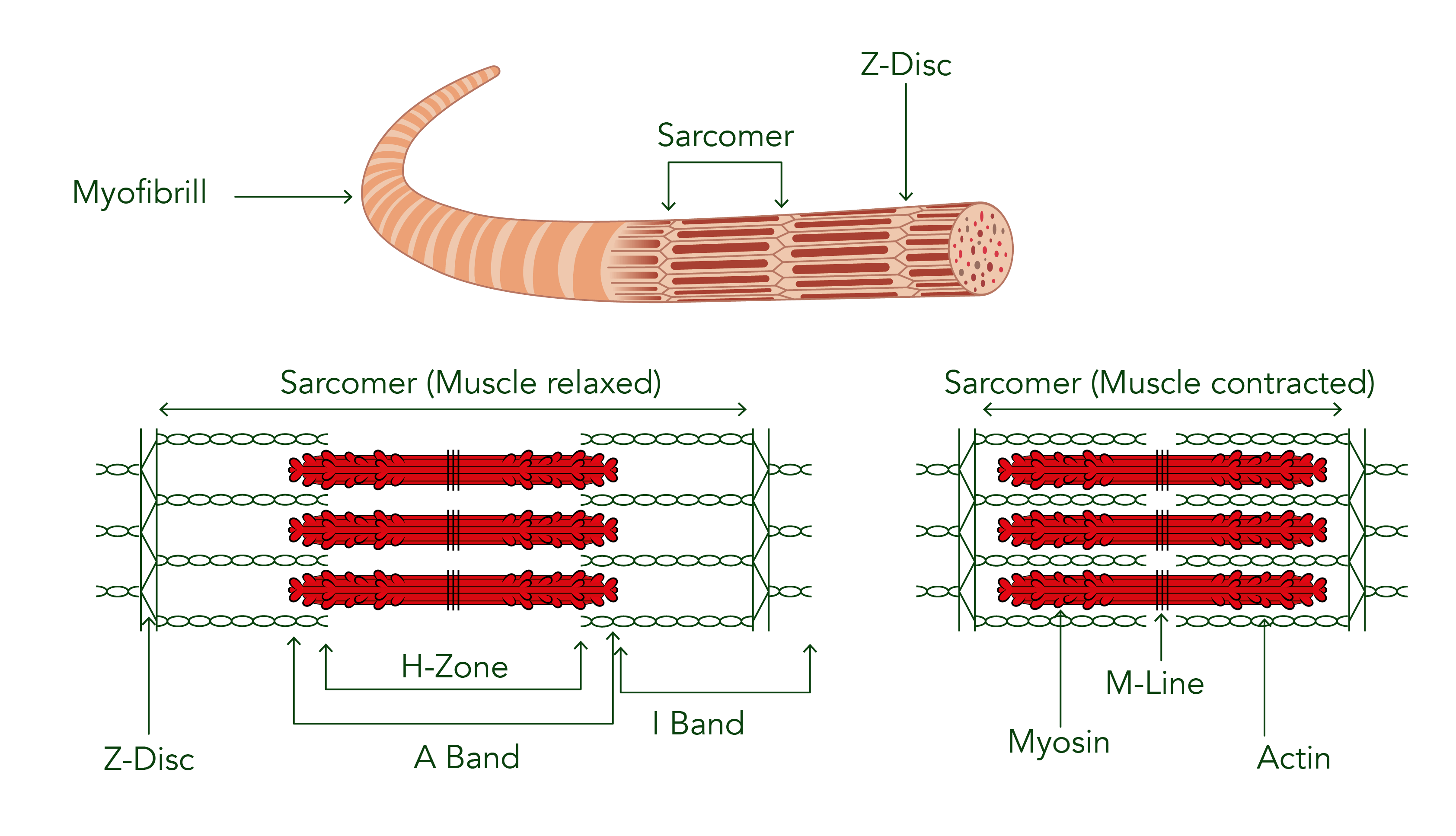

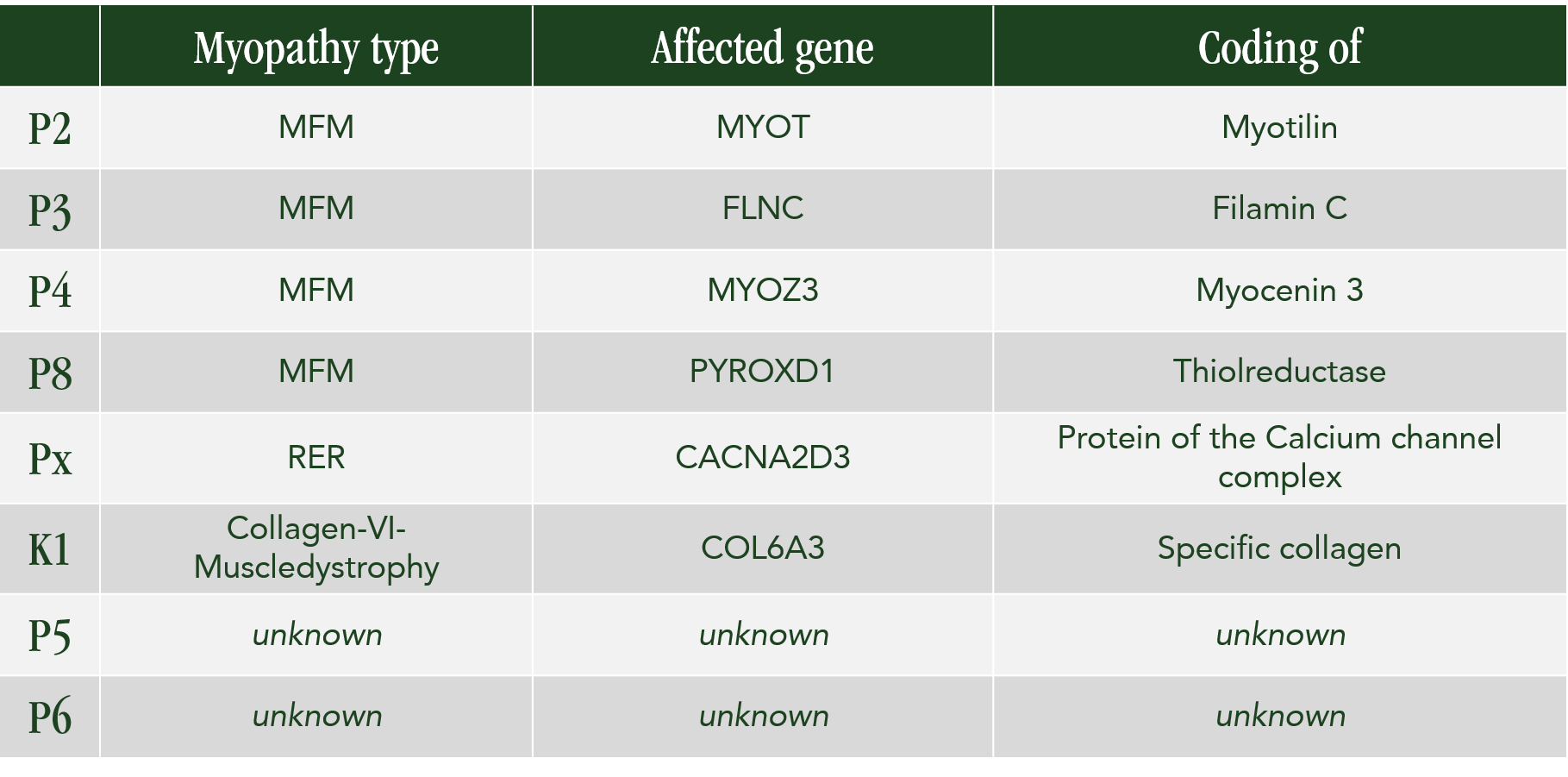

Figure 2: Schematic representation of a muscle fibril and a muscle cell (contracted or relaxed)

MIM (Muscle-Integrity-Myopathy), formerly "PSSM2"

The different variants

To date, six different MIM variants or gene mutations have been identified that are causative for equine myopathy. The P2, P3, P4 and P8 variants can cause myofibrillar myopathy, the K1 variant is associated with collagen VI muscular dystrophy and then there is the Px variant. These myopathies are each caused by specific altered genes, which in turn code for certain proteins and are thus causative for a disorder.

The affected proteins of the variants P2, P3 and P4 are structural proteins that are responsible for an instability of the Z-disk of the sarcomere (see Figure 3) due to the change or functional disorder, so that the muscle cell becomes unstable in itself.

Variant P8 is also an instability, but the affected protein is related to the protection of the cell membrane or the antioxidant defence, so that there is an increased need for antioxidants, especially vitamin E.

In the Px variant, a regulatory subunit of the voltage-gated calcium channel is affected, which is responsible for transmitting the nerve cell signal into muscle contraction, thus disrupting the electromechanical coupling. Horses with Px tend to be very excitable and nervous.

Collagen VI, which is affected in variant K1, serves as a protein of the extracellular matrix of the connection between the muscle fibres (endomysium). A genetic mutation also leads to instability or weakness of the muscle here.

Meanwhile, the variants P5 and P6 are also being discussed. However, these variants are alleles of the same gene (still unknown). This means that in addition to n/P5, n/P6, P5/P5 and P6/P6, P5/P6 is also possible in inheritance. However, in the case of n/P5 and n/P6, it is assumed that the affected horse will not develop any symptoms, as the alleles are recessive (not dominant).

It is remarkable that the different variants seem to express themselves differently (strongly) depending on the combination with other variants. The Px variant, for example, seems to reinforce the expression of the other variants. Therefore, it can be assumed that the different variants interact with each other.

Figure 3: Schematic representation of a muscle and its compartments including affected areas in MIM

The following table provides an overview of the different variants, the altered genes and the proteins affected by them:

Table 1: Overview of the MIM variants, the affected genes and corresponding proteins

Symptoms

Symptoms often appear for the first time between the ages of 7 and 10 years, although symptoms can also appear much earlier, in foals and young horses, if there is increased stress.

Unfortunately, the blood count gives little information about equine myopathies. While creatine kinase (CK), aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and possibly also creatinine, urea and potassium are acutely elevated in cross-myopathy (SER and RER), these values are often only slightly elevated or not elevated at all in horses with MIM.

The list of possible or typical symptoms is very long:

Phenotypically

- Muscle dents and tears

- "Washboard structure" (erroneously called "liver stripes")

- Fasciculation/muscle tremor

- Prominent spine

- Hypertrophic musculature forequarters

- Poorly muscled hindquarters

- Generally poor muscling

- Sudden weight loss in a short time

- Very high muscle tone

- In some horses also abnormally low body tension

The gait pattern

- Rope walk (placing the legs in front of each other as if the horse were walking on a rope)

- Bunny Hop" (rabbit gallop)

- Shivering

- Inexplicable, changing lameness

- Painful reluctance to move

- Ataxic movement patterns

- Pass in walk

- Loss of beat in turns

- Deceleration of the hindquarters

- Gait pattern similar to laminitis

When riding/working

- Sudden "explosion" out of nowhere

- Sensitivity to noise

- Fear of oncoming traffic

- Stiffness

- Increased sweating

- Leaning heavily on the hand

- Difficulties with load carrying (e.g. flying changes)

- Often very gaited and flashy young horses that become more and more problematic with further training

- Breathing noises very frequent

Behaviour

- Sensitivity to touch

- Unwillingness to be saddled, groomed, saddle compulsion

- Unwillingness at the farrier, especially when lifting the hindquarters for a longer time.

- Jumpiness

- Problems with hitching (poor balance)

- Changes in temperament

- Pseudo colic

- Difficulty getting up

- Horses no longer lie down (REM sleep deprivation)

Heredity

The mode of inheritance is autosomal semidominant with incomplete penetrance. This means that horses can already show symptoms with a heterozygous predisposition (e.g. n/Px). A combination of several variants is possible. Experience shows that the more variants there are (e.g. n/P2 + P4/P4 + n/Px) or if variants are homozygous (e.g. Px/Px), the earlier and more severe the symptoms appear. In principle, every breed can be affected by equine myopathy. A responsible approach to breeding should be a matter of course, whereby excluding affected horses from breeding is not advisable in order not to unnecessarily restrict the gene pool. However, equine myopathies can be reduced in the long term by conscious mating.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis can be made by muscle biopsy (MIM positive/negative) or genetic testing of the individual variants (usually via hair roots). However, the connection between gene mutation and symptom pattern has not yet been validated. The muscle biopsy of a horse with MIM shows clumps of glycogen molecules at sites of myofibrillar disruption. In practice, this means that the probability of a false-negative result is high if the tissue sample is taken from the wrong (i.e. unaffected) site of the muscle, as the glycogen clumps should not show up here. Even in young horses that have been tested as a precaution and do not (yet) show any symptoms, MIM cannot be ruled out by a negative muscle biopsy, as the corresponding changes in the muscles are difficult to show without symptoms.

How do I feed and manage a horse suffering from equine myopathy?

Husbandry and training

Horses with equine myopathies benefit from stress-free housing with sufficient moderate exercise. Standing days and stall rest are extremely counterproductive. Many myopathy horses are sensitive to weather and cold, which quickly becomes apparent through deterioration of the condition. Horse blankets can be useful here. Training should be adapted to the performance level, include long warm-up phases and avoid stressful performance peaks, although with proper management there is in principle nothing to be said against using the horse in competition.

Feeding

In principle, horses with equine myopathies should be fed a low-starch and low-sugar diet. For leisure horses and horses in maintenance need, < 10 % starch and sugar in the total ration, including basic feed such as hay and pasture grass, should be aimed for. As a rule, this can only be achieved by a grain-free ration (without endosperm). For sport horses, especially in high performance sport, up to 20 % starch and sugar in the total ration, including basic feed such as hay and pasture grass, can be tolerated.

For energy supply, structural carbohydrates ("fibres") and fats from cereal germs, oils and oilseeds should be resorted to. In addition, the supply of muscle-relevant nutrients such as magnesium, manganese and vitamin E is important. The need for protein or essential amino acids (especially lysine, methionine and threonine) is usually increased. Calcium should only be given to cover the needs of Px. Alfalfa is not tolerated by many horses with equine myopathy, although the cause of this has not been conclusively clarified. Pasture grass can also be problematic, but not necessarily (note: varying sugar content in pasture grass, depending on species composition, season, climate, etc.). Here, the individual differences are quite large and require "trial and error". In addition, affected horses often show stomach sensitivity and stomach problems, therefore the protection of the stomach should be taken into account in the ration design. A diet low in starch and sugar is therefore already beneficial for stomach protection.

In the following, the most important aspects of ration design for horses with MIM are clearly presented. These are recommendations that are partly scientifically confirmed and partly the result of practical experience. It should be noted that each horse must be considered individually - if only because of the various possible combinations of the MIM variants.

Table 2: Overview of important aspects (recommendations from science and practice) in the ration design of horses with MIM

Our power packs for the muscles are all:

Without added sugar, cereal starch and alfalfa

- Low-glycaemic (starch/sugar < 10 %)

- Easy on the stomach

- Suitable for horses with equine myopathies

- Also suitable for healthy sport and leisure horses

The optimal supplement

WES Bodyguard

- Muscle building and mineral feed in one

- Rich in lysine, methionine & threonine as well as manganese, magnesium, zinc & vitamins B, C & E

- Contributes to muscle development, better suppleness and performance

- For the healthy sport horse and horses with equine myopathies

WES Sensitive Bodyguard

- The soy-free Bodyguard

WES Energy Boost

- Mixture of linseed oil, rice germ oil and hemp oil

- Rich in valuable omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids and high-quality gamma-oryzanol

- For immune system, skin and coat

- Optimal for the energetic enhancement of the ration

WES Protein Booster

- High-quality protein concentrate for the supplementary supply of essential amino acids such as lysine, methionine and threonine

- Supports targeted muscle build-up

WES NanoShot E

- Water-soluble, natural vitamin E concentrate

- Highest bioavailability and stability through microencapsulation

- Antioxidant - promotes muscle energy metabolism and cell protection

- Particularly important for P8 and for impulsive horses

WES NoStress

- Highly efficient magnesium, vitamin B12 and herbal components for muscle and nerve function

- In potentially stressful situations such as transports, tournaments, stable changes, etc.

- Ideally suited for sport and leisure horses as well as horses with muscle metabolism problems

- Innovative liposomal encapsulation of the micronutrients

The basic feed - Mineralised

WES All in One

- Highly energetic, mineralised, grain-free and sugar-reduced muesli

- For the healthy sport horse and horses with equine myopathies

- Contains WES Bodyguard in sufficient quantity to cover the horse's needs

The basic feed - Not mineralised

Optimal in combination with WES Bodyguard or WES Sensitive Bodyguard or WES All in One

WES Basic Crunch

- High-protein and low-sugar basic feed (pelleted)

- For normal-fed sport and leisure horses

WES Power Crunch

- Energy- and protein-rich, low-sugar basic feed (pelleted)

- For sport and leisure horses with increased energy requirements or heavy feeders

WES Crispy Crunch

- High-energy, high-protein and low-sugar muesli

- For sport and leisure horses with increased energy requirements or heavy feeds

WES Sensitive Crunch

- High-protein and low-sugar basic feed (pelleted) without soy

- For normal-fed sport and leisure horses

WES Gastro Beet

- Particularly stomach-friendly basic feed for sport and leisure horses with sensitive stomachs

- Short swelling time

WES Sensitive Mash

- Tasty, protein-rich mash for stomach, intestine and well-being

- For horses with sensitive stomachs and digestive disorders

- Soy-free

Ricelein

- High-protein and low-sugar basic feed (pelleted)

- For heavy fed horses

GlyxWiese® Muesli

- Fibre-rich muesli without cereals

- For light fodder horses

If necessary or if symptoms occur, further supplements can help:

Magnesium B12

- For horses prone to stress to increase nervous resilience

- To improve nerve function, performance and concentration

- Especially important for Px

Makor® or Makor® LIQUID

- Highly dosed magnesium and vitamin E

- With circulatory stimulating hawthorn

- For all types of equine myopathies

Hesta Plus® Mangan or Hesta Plus® Mangan LIQUID

- Organically bound manganese

- For increased requirements due to tension and/or equine myopathies

- Especially important for P2 and Px

Personal feed consultation

We are at your disposal for a personal feed consultation and individual product combination.

Please contact us for this without obligation by phone or e-mail.

Telephone head office: +49 6222 990 100

E-Mail: info@st-hippolyt.de

Your St. Hippolyt Team

Specialist literature recommendation: Pferdemuskeln managen

(For now only in German language available)

Optimising musculature and well-being

- From recognising to understanding to practice

- Symptoms and diagnostics

- Training and feeding

- MIM (PSSM2)

- Available in our online shop

References:

Finno, C. J., Gianino, G., Perumbakkam, S., Williams, Z. J., Bordbari, M. H., Gardner, K. L., ... & Valberg, S. J. (2018). A missense mutation in MYH1 is associated with susceptibility to immune-mediated myositis in Quarter Horses. Skeletal muscle, 8(1), 1-13.

Fritz, K. L., McCue, M. E., Valberg, S. J., Rendahl, A. K., & Mickelson, J. R. (2012). Genetic mapping of recurrent exertional rhabdomyolysis in a population of N orth A merican T horoughbreds. Animal genetics, 43(6), 730-738.

Guthöhrlein, K. (2023). Pferdemuskeln managen. FN Verlag. Warendorf.

Kentucky Equine Research (KER)

Lewis, S. S., Nicholson, A. M., Williams, Z. J., & Valberg, S. J. (2017). Clinical characteristics and muscle glycogen concentrations in warmblood horses with polysaccharide storage myopathy. American journal of veterinary research, 78(11), 1305-1312.

Maile, C. A., Hingst, J. R., Mahalingan, K. K., O'Reilly, A. O., Cleasby, M. E., Mickelson, J. R., ... & Piercy, R. J. (2017). A highly prevalent equine glycogen storage disease is explained by constitutive activation of a mutant glycogen synthase. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects, 1861(1), 3388-3398.

McCue, M. E., Armién, A. G., Lucio, M., Mickelson, J. R., & Valberg, S. J. (2009). Comparative skeletal muscle histopathologic and ultrastructural features in two forms of polysaccharide storage myopathy in horses. Veterinary pathology, 46(6), 1281-1291.

McCue, M. E., Valberg, S. J., Jackson, M., Borgia, L., Lucio, M., & Mickelson, J. R. (2009). Polysaccharide storage myopathy phenotype in quarter horse-related breeds is modified by the presence of an RYR1 mutation. Neuromuscular Disorders, 19(1), 37-43.

McCue, M. E., Valberg, S. J., Lucio, M., & Mickelson, J. R. (2008). Glycogen synthase 1 (GYS1) mutation in diverse breeds with polysaccharide storage myopathy. Journal of veterinary internal medicine, 22(5), 1228-1233.

McCue, M. E., Valberg, S. J., Miller, M. B., Wade, C., DiMauro, S., Akman, H. O., & Mickelson, J. R. (2008). Glycogen synthase (GYS1) mutation causes a novel skeletal muscle glycogenosis. Genomics, 91(5), 458-466.

Valberg, S. J., Cardinet III, G. H., Carlson, G. P., & DiMauro, S. (1992). Polysaccharide storage myopathy associated with recurrent exertional rhabdomyolysis in horses. Neuromuscular disorders, 2(5-6), 351-359.

Valberg, S. J., Finno, C. J., Henry, M. L., Schott, M., Velez‐Irizarry, D., Peng, S., ... & Petersen, J. L. (2021). Commercial genetic testing for type 2 polysaccharide storage myopathy and myofibrillar myopathy does not correspond to a histopathological diagnosis. Equine veterinary journal, 53(4), 690-700.

Valberg, S. J., Henry, M. L., Perumbakkam, S., Gardner, K. L., & Finno, C. J. (2018). An E321G MYH1 mutation is strongly associated with nonexertional rhabdomyolysis in Quarter Horses. Journal of veterinary internal medicine, 32(5), 1718-1725.

Valberg, S. J., McKenzie, E. C., Eyrich, L. V., Shivers, J., Barnes, N. E., & Finno, C. J. (2016). Suspected myofibrillar myopathy in Arabian horses with a history of exertional rhabdomyolysis. Equine veterinary journal, 48(5), 548-556.

Valberg, S. J., Mickelson, J. R., Gallant, E. M., MacLeay, J. M., Lentz, L., & De La Corte, F. (1999). Exertional rhabdomyolysis in quarter horses and thoroughbreds: one syndrome, multiple aetiologies. Equine Veterinary Journal, 31(S30), 533-538.

Williams, Z. J., Bertels, M., & Valberg, S. J. (2018). Muscle glycogen concentrations and response to diet and exercise regimes in Warmblood horses with type 2 Polysaccharide Storage Myopathy. PloS one, 13(9), e0203467.

Wu, L. E., Levina, A., Harris, H. H., Cai, Z., Lai, B., Vogt, S., ... & Lay, P. A. (2016). Carcinogenic chromium (VI) compounds formed by intracellular oxidation of chromium (III) dietary supplements by adipocytes. Angewandte Chemie, 128(5), 1774-1777.

www.equiseq.com, last view: March 2023

www.generatio.de, last view: March 2023